This article is written by Matt Soergel, and originally published in the Florida Times Union. Photography by Will Dickey.

Before the journey to the moon changed everything, William Van Duyn, like many of the senior chemical engineering students at the University of Florida, had a job lined up after college: He’d go work in a paper mill: A good, solid career.

But it was 1961, and President John F. Kennedy, in a speech to Congress, promised to launch the U.S. on “a great new American enterprise” — landing a man on the moon, and bringing him home safely, before the end of the decade.

It would be difficult and expensive, Kennedy said, and would require the efforts of the entire nation: “All of us must work to put him there.”

So when aerospace recruiters came to campus, Van Duyn was ready. No paper mill for him.

Instead Van Duyn, the eldest of four children, had to tell his widowed mother in rural Mandarin that in a few days he was leaving for California, to work on rocket engines in America’s race to the moon.

Six years later, he headed home to Florida, to Cape Canaveral, one of tens of thousands of men and women trying to figure out how complete that quest.

Van Duyn would rise to become a lead engineer on the second phase of the Saturn V rocket that carried astronauts into orbit. He worked on all the manned Apollo missions, including Apollo 11, which put astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin on the moon on July 20, 1969, beating Kennedy’s deadline by several months.

He was 31 then, 81 now, and looks back on that part of his life with quiet satisfaction.

“There’s not too many of us left to interview. I was one of the young guys,” he said. “I got to launch every man who ever went to the moon.”

•••

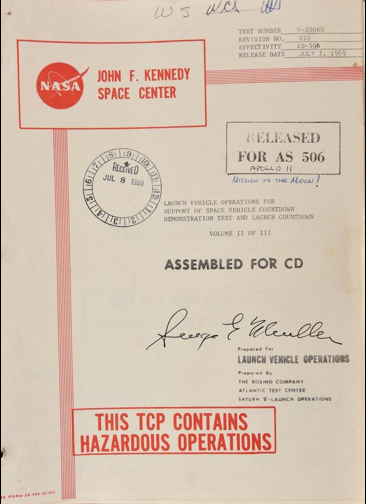

At his Orange Park home, Van Duyn pulled out a three-ring binder, thick with hundreds of pages. “My hunch is this is rare,” he said.

Inside the binder is the launch manual for Apollo 11, with detailed instructions — indecipherable to the layperson — of the thousands of steps and checks taken in the long hours before liftoff. Van Duyn got his copy on July 8, 1969, and somewhere along the line, wrote on the cover: “APOLLO 11. MISSION TO THE MOON!”

Everyone in the firing room at Cape Canaveral had one, and everyone had an assignment listed inside. Though there were windows that looked out on the rocket, you didn’t have time, he said, to gaze at the launchpad. You didn’t have time to ponder that you were in the midst of a historic mission.

You had a job to do.

Van Duyn’s was monitoring the second stage of the Saturn V, the most powerful rocket ever launched.

The first stage, on the morning of July 16, 1969, shot the Apollo spacecraft off the launchpad until its fuel was expended. The second stage, fueled by liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen, took over and propelled the rocket into the thin atmosphere, before it too broke off and fell in the ocean. The third stage then took the craft into orbit.

And when Van Duyn’s stage kicked in?

“Goosebumps all over. But you couldn’t stand there and go woo-woo-woo,” he said. “All through the flight I had to stay on my panel and watch certain instrument readings on there for any problems.”

Van Duyn was one of the many engineers monitoring a console in the firing room, each in a white launch jacket with a company name on the back. His, in black letters, said “Rocketdyne.”

He wants people to understand the importance of the private companies that worked on the moon launches. “NASA was the program manager,” he said. “They did not build spacecraft, they didn’t build spacesuits, they didn’t build rocket engines. They were managers. And they did a dadgum good job of it. That was their contribution, because pulling all these people together, hundreds of contractors, and on that tight schedule, was a major miracle.”

He joined North American Aviation’s Rocketdyne division in 1961, testing rocket engines in a valley north of Los Angeles. He didn’t like California — the smog, the way of life — though he did meet his future wife, Linda, a native Angeleno, at a church in North Hollywood. He wanted, badly, to go back to Florida.

So he landed a job with another company working at Canaveral; the work wasn’t as interesting but it got him home. But his boss at Rocketydyne tore up his resignation letter and and threw it the trash. He told Van Duyn: We’ve got people in Florida now, and you’ll join them.

In 1967, the Van Duyns came to the Cape, where people worked hard and played hard, especially down in Cocoa Beach. He laughed: “It was something else. There was the space program side of it, then there was the, uh, social side.”

They weren’t really looking for that, so they settled farther north in Titusville, close enough that he could sometimes bicycle to the Vehicle Assembly Building, the gigantic structure inside where the rockets to the moon were assembled. It was a good life, the Van Duyns said, for them and their three children.

William Van Duyn and others often worked 70-hour weeks, but you felt, he said, as if you were part of something momentous. “Absolutely. No doubt. Everyone knew what their part was.”

“Even the families were part of it,” Linda Van Duyn said. “As a matter of fact, my children learned to count backwards, 10-9-8-7-6-5-4-3-2-1, before they learned to count forward.”

•••

More than four days after the Apollo 11 spacecraft was launched, the Van Duyns watched the landing and moon walk on TV, from the home of his mother, Ruth.

His Van Duyn ancestors were Dutch, and date back to 1649 in New Amsterdam, now New York. “We stayed there ’til the English ran us out,” he said. “Then we went to New Jersey.”

His father, Abram, was a field auditor for an insurance company, and took his family with him as he traveled from place to place. For young William’s early years, the family didn’t have a settled home and lived mostly in hotels. “Before I was 5 years old, we’d been every state in the United States, Mexico and Canada, some many times,” he said. “I have to think that was influential.”

They moved to Mandarin in 1949. It was country, with miles of piney woods between it and Jacksonville, and it suited William, who went fishing and began building boats. From an early age, he was a tinkerer, building things, fixing things, modifying things, including rebuilding his family’s old English Ford Prefect from the ground up. That came from both necessity (the family didn’t have much money) and aptitude (he wanted to see how things worked).

He went to Jacksonville University for two years, but quit to help care for his family after his father died at 49. A year later, he went on to Gainesville, to UF. He wanted to be a fighter pilot but was an inch shy of the 5-foot-8 minimum height, so he took up chemical engineering.

Working at Cape Canaveral took every bit of his natural ability and years of training. IBM mainframes as big as a room printed out the manual they used, he said, but back then getting a ship to the moon and back was done largely with blueprints and slide rules.

“We got to the moon on a slide rule, basically,” Van Duyn said.

Much of the work was hands-on: Inside the Vehicle Assembly Building, he took frequent trips up in the cage elevator, to dizzying heights, to walk out on a swing-arm to the looming rocket, as tall as a 36-story building. It was high-pressure work, on well-nigh impossible deadlines.

“I had a work crew out there. We did a lot of engine modifications out on the launchpad. They were supposed to be done before we even got to Florida, but it was an R&D program, you know? We were supposed to get there by the end of the decade, and we did things in a very big hurry.”

Van Duyn jokes of the frequent calls he got from concerned bosses at Rocketdyne. Everyone’s waiting, they’d say. When are you going to get done?

“I said, ’Well, the reason we can’t get any work done is because everybody keeps calling from California, and they want to stay on the phone for a half-hour. Please, if you need to call us, make it quick — ‘cause I’ve got to go back in there and work, and we’ve got to get to the moon somehow.’”