Written by March 17, 2022

University of Florida researchers have invented a test that can determine within 10-15 minutes whether patients test positive for COVID and, if so, which of the five known variants of concern they have.

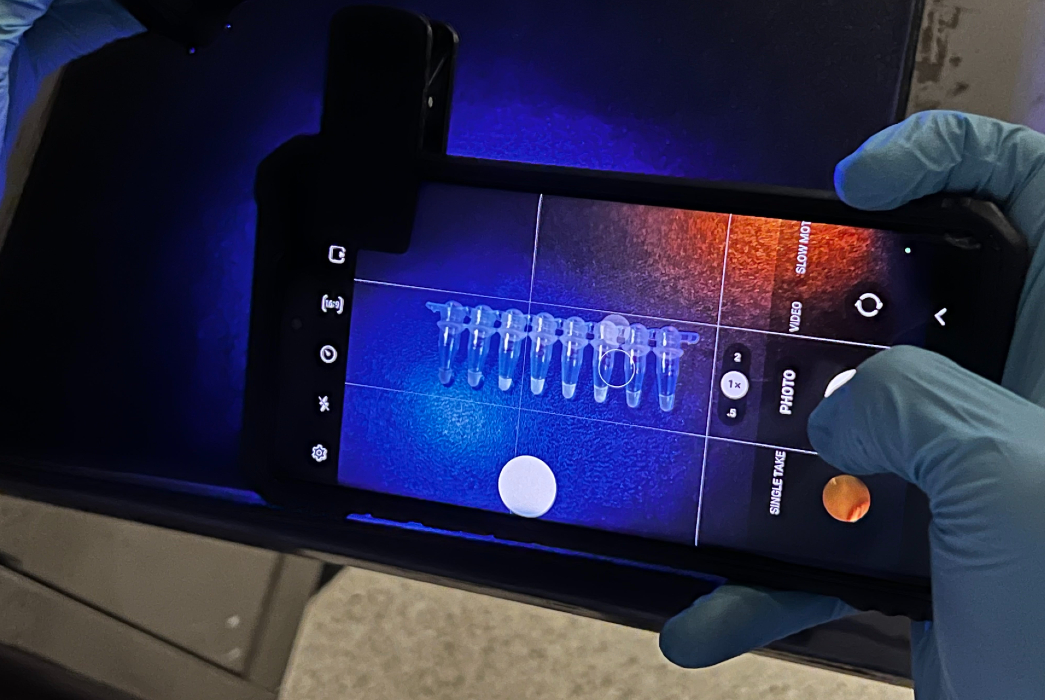

The research, published Saturday in The Lancet’s eBioMedicine, involves the use of a simple heating device and a cellphone. The team also used a new form of CRISPR — a means of finding and targeting a specific section of genetic material inside a cell — to quickly and effectively diagnose COVID and learn which variant of concern is in a patient sample: alpha, beta, gamma, delta, or omicron.

The finding could provide policymakers with vital information about when to require masking and prepare hospitals for a wave of infections. It could also allow patients and family members to prevent or treat a particular variant more effectively.

“For the medical and research community, knowing which variants are emerging is extremely important,” said corresponding author Piyush Jain, an assistant professor and a Shah Rising Star Professor in the Department of Chemical Engineering. “If an especially serious variant like delta or a genetically similar variant, such as deltacron, arises in the future, work like this discovery will help us track it earlier.”

The team, including professors Marco Salemi, Rhoel Dinglasan, John Lednicky and their lab members from the Emerging Pathogens Institute, made the findings in collaboration with two bioscience engineering companies registered in the Czech Republic. The companies helped the researchers engineer a prototype that could function at home, in a clinic, or in the field.

Current processes for determining COVID variants take several days to perform, which is why patients typically don’t learn which variant they have.

Advancing on recently published work, including by Long Nguyen, a PhD candidate and the first author of the study, the UF team is the first to investigate the new heat-loving CRISPR technology, which manages to combine speed, accuracy, and variant identification by amplifying and detecting coronavirus genetic material in one step.

The team also created a version of the test that can potentially be used at commercial testing centers, or even at home, and can be stored at normal temperatures for weeks and activated by adding water.

Researchers validated the test in hundreds of clinical samples, detecting all five variants with 97% accuracy within 30 minutes.

Jain, who says he hopes the product can be brought affordably to market soon, also worked with Dinglasan, a professor of Infectious Diseases & Immunology, and others to establish a startup called Genable Biosciences, LLC, centered around finding partners to manufacture and commercialize the new product.

Such groundbreaking and interdisciplinary work helps to prepare for future infectious disease outbreaks, said Salemi, a professor of pathology and member of the research team.

“Requiring expertise in biochemistry, molecular virology, and genomics, this work is an example of how the COVID pandemic has fostered collaborative research to unprecedented levels,” Salemi said. “I think what we have learned about rapid detection and surveillance of fast-spreading and mutating pathogens like SARS-CoV-2 will be crucial to face the challenge of future pandemics with strong intervention measures already in place.”